|

I'm still in recovery mode from spending 3 of the best weeks of my life at the Bang on a Can Festival at MASS MoCA in North Adams, MA. It was pretty much the ideal life: spending all day playing weird, new music in a contemporary art museum. Above, I'm preparing to play Amanda Schoofs' piece, Fragility of Permanence underneath the breathtaking phoenix sculptures by Xu Bing. A really gracious and talented group of musicians agreed to play my piece, touch, in a gallery recital. Here we are playing amongst early Sol LeWitt.

From left to right, the ensemble is: Stephanie Richards, trumpet Lina Andonovska, flute Adrianne Pope, violin Ted Babcock, vibraphone Jacob Abele, toy piano Chuck Furlong, bass clarinet Doug Machiz, cello (me) Zeca Lacerda, vibraphone Ken Thomson, bass clarinet The fantastic Madison-based label Mine All Mine Records, in collaboration with Grimmusik, is releasing a compilation this week of ambient and experimental music. I've contributed a track, and it's an honor to be included. The release features tracks from many stellar musicians, including Thollem McDonas,CJ Boyd, Brothers Grimm,Pat Reinholz, and many, many more. The album will be streamed live TOMORROW at MIDNIGHT on Gross Time. There's an album release show on Friday night in Madison, that's going to be amazing. In other news, Kirsten Carey has released the second of the four videos we shot from her Ulysses Project last month. We spent three days in the studio this past weekend recording the entire album, and I'm excited to say that it's going to be totally kickass. If you haven't yet donated to her Kickstarter to ensure completion of the album and reserve your copy, DO IT!!!!

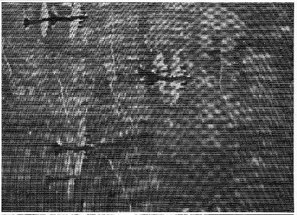

I failed to post this here a few months ago, but here is a very short film I made with my Thad Curious partner, Ryan Epp: I’m going to start out this post by writing about the work of the artist Christiane Baumgartner. Baumgartner is a visual artist, and the medium that she works in is woodcutting. Woodcutting is a long, taxing process that requires a great deal of cumbersome equipment, and each woodcut requires hours of work. In this age of mass reproduction, it’s an anachronistic medium--actually, it’s one of the oldest ways that images have been reproduced. Baumgartner doesn’t always work with ancient methods. While she learned the art of woodcutting first, she then broke into the field of digital video art. Following that, it seemed a natural progression for her as an artist to explore combining the two mediums. This is where things get particularly interesting. It seems so simple, but this act of combining this extremely modern medium, video, whose rewards are immediate and ubiquitous, with this old, laborious process whose rewards are painstakingly slow is so effective. In her woodcuts, she recreates digital stills, which she does by making many lines of varying thickness. This is a very simple way to represent very complex images. She often captures the images by filming a playing video, which creates a digital interference, which she is able to recreate in her woodcuts. In this way, her very medium is infused with meaning, and the statements her pieces make is heavily enforced by the process by which they were created. This efficacy is evident in viewing these images over the Internet, but in seeing them in person, these large woodcuts are pretty astounding. I won't bother going into an exhaustive analysis of her work, breaking down the intricate double codings taking place, but I hope you look into exploring more of her work. (A good interview with Baumgartner can be found here.) And from that discussion of a really great artist, I'd like to transition to talking about my own work. Hm. Well, here goes... In our piece exit crafting, Anna Weisling, Eric Sheffield and I hoped to create a piece that conveyed an effective experience to the audience. The process we used to develop the piece was one of performative collaboration--starting from some snippets of musical material I'd developed, we three sat down together and honed the segments of the piece into something that felt right, by playing through things together, giving each other feedback, and developing our own parts. Here's a video of us performing for a class at UW-Whitewater in December: The presentation of this piece is similar to that of much contemporary classical music. We premiered the piece at the Electroacoustic Juke Joint in Alabama in November. There was a lot of great music at that festival, but our piece stood out because of the process by which it was created. This is the connection I want to make with Baumgartner's woodcuts--that the process hopefully infuses the work with another layer of efficacy. I don't think that this is an inexperiential, intellectual efficacy, I think that the event of the performance is notably affected by this process. We developed the piece together, and we perform it together--not to appease the composer, but for a collective contribution to the piece itself.

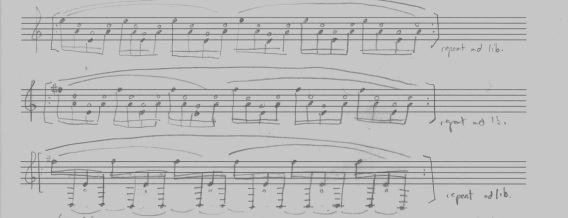

Here are my 'formal' notes on exit crafting: exit crafting collaborative performance by Ben Willis, double bass Eric Sheffield, electronics, guitar Anna Weisling, visualizations The process for creating exit crafting was/is a collaborative one. That is, each member of the ensemble is responsible for their own part, and, in composition, responsible for effectively reacting to and critiquing the other parts of the ensemble. To those of us musicians who have been involved in musical groups within ‘popular’ idioms, such as rock bands, and, to an extent, jazz combos, this process doesn’t sound unfamiliar in the least. But in the world of Western Classical music, which is instilled with a separation of composers and performers--the idea that there is one composer, and the ensemble has only the creative liberty to interpret the piece--this process is rarely seen. The compositional language of exit crafting is intentionally located in a space between ‘art music’ and ‘popular music.’ The harmonies created are largely consonant, often based around fourths, fifths, triadic and tonal-sounding material. Formally, each section works through a series of changes--the first a gradual evolution of the pitches ascending in the bass, the second a series of sections that treat similar material in several ways (a repeated arpeggiating guitar pattern with melodic bass sounds layered on top), and the third a sort of merging of the two: sections that are different and moved through gradually elaborated material, but based in a distended pop-song form of verse-chorus-bridge, but is stretched in a way that disallows the sections from being repeated. The video element of exit crafting ties the material into a combined sensory experience. The video material was developed alongside the musical material, rather than sculpting one to fit the other, as when music is written for films, or music videos are made to complement pre-existing music. Like a lot of Americans, this week I headed Home (not to be confused with my home of Madison) to spend a few days with my parents. (Sure, the holiday of Thanksgiving has a sordid and not entirely wholesome history, but its purpose and role today is one of the purest of holidays: relatively free of commercialism and religious dogma, it's an opportunity to celebrate and appreciate the company of others.) For me, Home is the icy tundra of rural northwest Minnesota. I left Madison on Monday 45 degrees and raining, and found Pennington County eleven hours later 2 degrees and snowing. Spending so much time isolated in a vehicle--often on deserted country roads, staring into the bleak darkness through splatters of ice that were quick to form on the windshield--provided a great opportunity to spend some time reflecting on the slurry of events that preceded this week. On Nov. 12, I had an adventure driving a different direction, due south, to Florence Alabama, to perform at the Electroacoustic Juke Joint festival. This was my first real experience traveling to perform at a music festival, and I couldn't be more glad this was the one. Everything added up: I was visiting a state I'd never been to before, (one warmer than the one I live in) I was traveling with two of my dearest friends and favorite collaborators, Anna and Eric, and I got to hear some new and creative music by a very inspiring and personable group of talented composers. The event was hosted by composer/performer Mark Snyder, a really amazing person who was gracious enough to put us up at his house, and whose heartwrenching pieces represented some of the best moments of the weekend for me. (A composer after my own heart, he's actually written a bass concerto!) All of the other composers and performers at the festival were amazing as well, and I highly recommend spending some time looking them up through the EAJJ website. We made the trek back north on Sunday, Nov. 15th, and arrived in Madison at about 3:30 Monday morning. I took a shower, threw on a shirt and tie, and got a ride to the airport, (thanks, Pat) from whence my plane departed at 6 for Hartford, CT. (I wear a tie and jacket when I fly, because I've found that I'm treated much better that way. Go figure.) While at Hartford, in sort of an excited haze of adventurous sleepiness, I met and had a lesson from a hero of mine, Robert Black. I also got to hang out with the bass studio there, and sit in on Professor Black's free improv class. Really inspiring! That evening, I hopped the bus to Boston. I went to Boston to visit a dear friend of mine from back North, Derek. Derek's a bang-up violist--really probably the best musician I know (don't tell anyone) -- and spending time with him is always really great. While visiting, I got to sneak in to the MFA (thanks to Chris, whose student ID we found on the street), take in an amazing concert at NEC that celebrated Gunther Schuller's 85th birthday, visit a great (if a bit claustrophobic) used and rare bookstore, and see the aquarium. (In case you'd forgotten, sharks are terrifying.) Gunther Schuller's music is some of the greatest I've heard, and his level of talent and sense for detail are mindblowing. Here's a great interview with Schuller by Ethan Iverson. It's lengthy, and worth it. Here's a video of me performing his Quartet for Double Basses at the Richard Davis Foundation Bass Conference this past April with some of my UW bass comrades (feel free to skip to 1:45 to get past my blithering at the beginning): I flew back to Madison on Thursday, Nov. 18th, where I had to almost immediately run to the tech rehearsal for the UW Dance Faculty recital that was on Friday and Saturday. The Weather Duo made an original piece of music to accompany a piece for choreographer Li Chiao-Ping. This was a really exciting project for us--it's really amazing to work with a dance, trying to come up with material that is appropriate, but not distracting, interesting, but not busy. Li Chiao-Ping's piece was an amazing and complex display of interlocking and contrasting movements. The dancers were really impressive. Here's the Isthmus review of the Friday performance. It is very positive about Chiao-Ping's piece, which is exciting, and the Weather Duo even gets a flattering mention. ("Engrossing!" -Isthmus) It describes well the other pieces on the program also, which I was really happy to be able to see three times. Especially notable for me was "Here/So (12 lines)" by Bill Young. The piece covered a lot of ground, from humorous and sporadic dog-barking, to really moving and eerie interactions. Also great was Jin-Wen Yu's "March Into Sunlight," which featured not only great narrative choreography and nice use of projected visuals, but the music of Prof. Steve Dembski (played live by the Gramercy Trio) and the dancing of my great pal Kenny, who can be seen on my left in the video above! Getting a preview of the holiday season, that weekend marked the start of rehearsals for A Wonderful Life, which is being put on by the Children's Theater of Madison this December. As much as I love avant-garde and challenging music and art, good old musical theater can be really refreshing sometimes. The music for A Wonderful Life is surprisingly fun and endearing, and the people involved are great. As one more artistic treat before embarking for Home, I contributing some bass tracks to a project of ambient guitarist Chris Bocast. The atmospheres he's creating with this project are really beautiful, and I can't wait to hear the finished album. And this brings me back to where I started this post, in the blustery plains of rural Minnesota. It was really peaceful and centering to spend some time up in the white silence, with time to read and get a grasp on who I am. I spent 18 years of my life waiting to leave my home town, but whenever I go back, I feel like a sea turtle surfacing to fill my lungs with air for another plunge out into the real world. Sea turtles can stay underwater without breathing for like 10 hours--holy shit! Something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately in regards to my own playing is the role of control. I recently listened to an episode of the New Yorker: Fiction podcast in which Salvatore Scibona was discussing the fiction of Denis Johnson (I confess to not being at all familiar with either of these authors before hearing the podcast) and, in describing the flowing, free way Johnson’s prose comes off--coming off so well that it seems to be extremely well planned--Scibona quoted a writing teacher of his as saying “Control is what produces the illusion of freedom.” For musicians, it is often a goal to play in a manner that seems effortless, free, uninhibited. To appear as though we play with ease. There are certain pieces for which this is not a goal--Andriessen’s Workers Union and Rzewski’s Coming Together come to mind. (An aspect that I really love about both of these pieces is that they’re designed to make the musicians struggle, and for my tastes, an effective performance of either requires the players to be beating themselves to shit.) This is why performances of the Bach cello suites on double bass are never truly effective--because they require so much struggle (excess shifting, awkward double-stop positions), even the best players can’t help but sound like they’re working hard. That’s not to say they should stop trying--I sure won’t--but I’m waiting for someone to prove me wrong. Playing in an effortless, free style ironically requires an extreme amount of grueling practice to be done successfully. This is a concept that I can’t help but apply generally to the notion of “free improvisation.” Of course, effective free improvisations require an extreme amount of control on the part of the performers, especially since often they will utilize a great deal of extended techniques, and need to use a great deal of ear power if playing with other musicians. Partially in exploration of this, I’ve done a guided improvisation, very creatively titled ‘Open A,’ wherein I play with the notion of control. By creating a set of guidelines, and using techniques that I’ve been working on for some time (I like to think that they’re hard, at least) I’ve tried to create a piece that sounds flowing and loose, while at the same time, working fairly hard for it. I’m not going to say if I’ve succeeded or not, but I will provide two different takes of this, that will hopefully work to illustrate these ideas. I’ve uploaded the first take as a video, and the second take as audio. This, I think, will help to separate them in terms of judgement, creating two different sorts of experience so that they can’t be as directly compared to each other. Here’s the first take, as a video: Open A from Ben Willis on Vimeo. I’ve also described my guidelines in greater detail on the Vimeo site. Here’s the second take, audio only: You may notice, if you’ve read the rules, I break more of my own rules in the second take. I’m not sure if this makes the performance more or less effective. Many thanks to Anna Weisling for her help in making the recordings and the video. |

Authorbassist/improviser/ I send emails occasionally about upcoming performances. They're very cordial.

FriendsAnna Weisling

Anna Vogelzang Brothers Grimm Dave Wells Derek Worthington Dylan Chmura-Moore Eric Sheffield el-tin fun Jeff Herriott Jerry Hui Jonathan Kuuskoski Kirsten Carey Luke Polipnick mine, all mine! records New Muse Patrick Breiner Peter Mackie Pushmi-Pullyu Surrounded by Reality Tom Teslik Thistle Categories

All

Archives

February 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed